This article was spawned by "an incident", where I did something I'd never done before... I got so fed up with a piece of code that had been bugging me for way too long, and when it blew up with a big fat YSOD1 yet another time, I closed (slammed, ed.) the lid on my MacBook Pro, threw it in the bag and went home.

Of course, I tweeted it and got some encouraging words from my awesome friends on Twitter, and a few suggestions of things to do instead :)

So later, while walking the dog, I thought of a couple of really awesome guitar-riffs that would kind of reflect my feels toward the dreaded YSODs of the day. They sounded awesome in my head - Metallica-style riffs with Chris Cornell (RIP) screaming on top!

I also tried to come up with alternative meanings for the acronym; e.g., songtitles like "You Said Over Drive" or "Yesterday's Stage Opera Delighted" - please send me any good ones of your own on a tweet-sized postcard :-)

But then all of a sudden, I started thinking about going all the way and somehow channel it into composing a little piece of music, using a very specific technique that sits well between the very strict programming world and the very loose world of music...

But first, let's digress...

While I was studying to be a music teacher2 we had a very famous (i.e., "hotshot") sax player visit the music conservatory for a workshop, and in the Q&A section at the end, everyone was asking questions like "what's your favorite scale to play over a dominant 7 altered chord?", or "what is the most efficient fingering for a C# augmented triad arpeggio?".

"Oh. My. God."

— Janice

But at some point, a seemingly misplaced hard rock guitar player (yep, yours truly) asked a question: "What do you do when nothing's working or you just don't feel you're getting anywhere with a piece of music or an exercise? Do you go for a walk in the woods, climb a tree or something like that?"

His answer baffled me — he said that he usually just switched to another song/piece or exercise and that "there is always an exercise you haven't played recently".

To me that was such a strange answer — now I don't know if he was completely honest, or if he was just saying this because he was at a music conservatory where everyone is pretty much 99% into all things music for four years, and he figured it was a better answer, but man! Why wouldn't you at least try something completely different just for a couple of hours (or days even), if it could give you a new perspective, or perhaps just a break from what you're maybe a little stuck doing?

Anyway - back to the main story where I chose to at least try something completely different :-)

4-Tone Technique

Inspired by a very well-known classical technique — the 12-Tone Technique — I decided to find the four notes, that represent the letters Y,S,O & D and compose a little piece of music, using the basic rules of the 12-tone technique. 3

Four New Best Friends

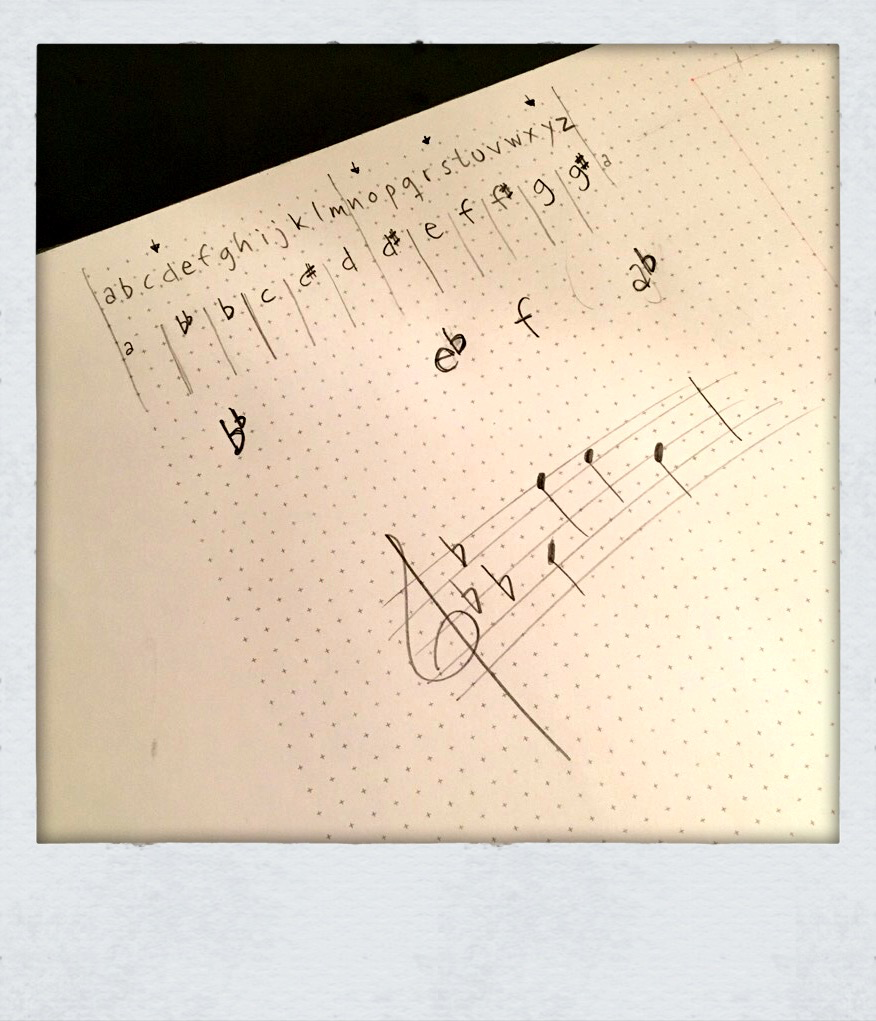

So finding which 4 notes to use, I did what every programmer would do - list the alphabet (26 letters), and below it evenly spread the 12 notes of the chromatic scale and see where the letters line up. (You do this on paper, of course — unless you're really good at getting one-liners in Terminal/Console right the 1st time4 :-)

Fortunately, I didn't have to make any "artistic" decisions, as the letters I needed fell on quite obvious notes - yay!

So a♭, f, e♭ and b♭ were the lucky four!5

Rules & Sequences

When you compose using this technique, you can think of it a little bit like copying & pasting four related sequences over and over again to create the final piece; you can't change the order of the notes, but the lengths and rhythms, meter, tempo, force etc. are all up to you. Normally, even the initial sequence of the notes is up to you, but a YSOD ain't the same as a DOSY, so… :-)

So here's the very quick summary of the "rules":

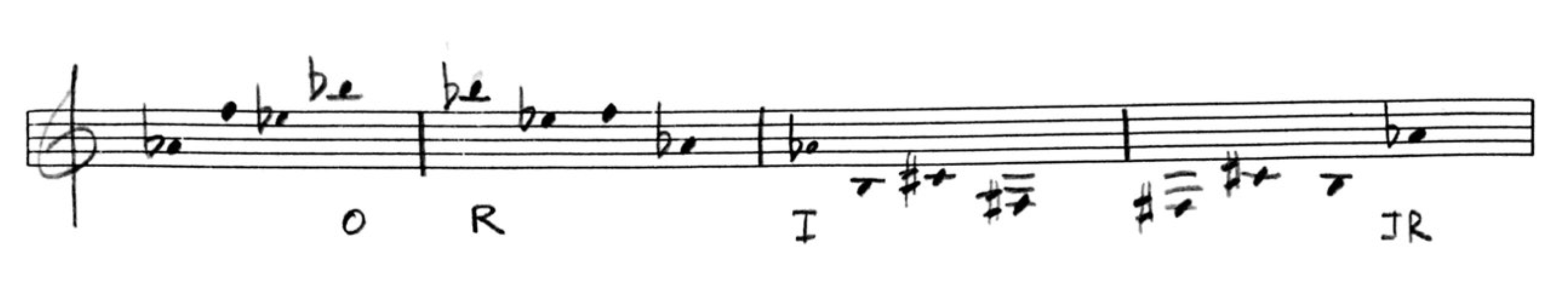

- Create the "master" (origin) sequence, and from that:

- Create the retrograde version

- Create the inverse version

- Create the inverse retrograde version

The retrograde version is constructed by playing the sequence backwards, while the inverse means that you start on the same note as the origin, but instead of going up a number of half-steps to reach the second note, you go just as many half-steps down - repeat for the remaining notes in the sequence. By now, you can probably guess how the inverse retrograde gets constructed...

-

Use these 4 sequences to compose a short or long, 1- or 20-voice piece of music that's soft, loud or mellow and fast/slow with as many different instruments as you prefer - simple, right? :-)

The resulting sequences looked like this:

Compose!

Well, as someone clever probably once said:

Four related sequences does not a piece of music make

So I took the origin sequence and started playing the notes on my guitar in a multitude of variations until I started to hone in on a motif I liked:

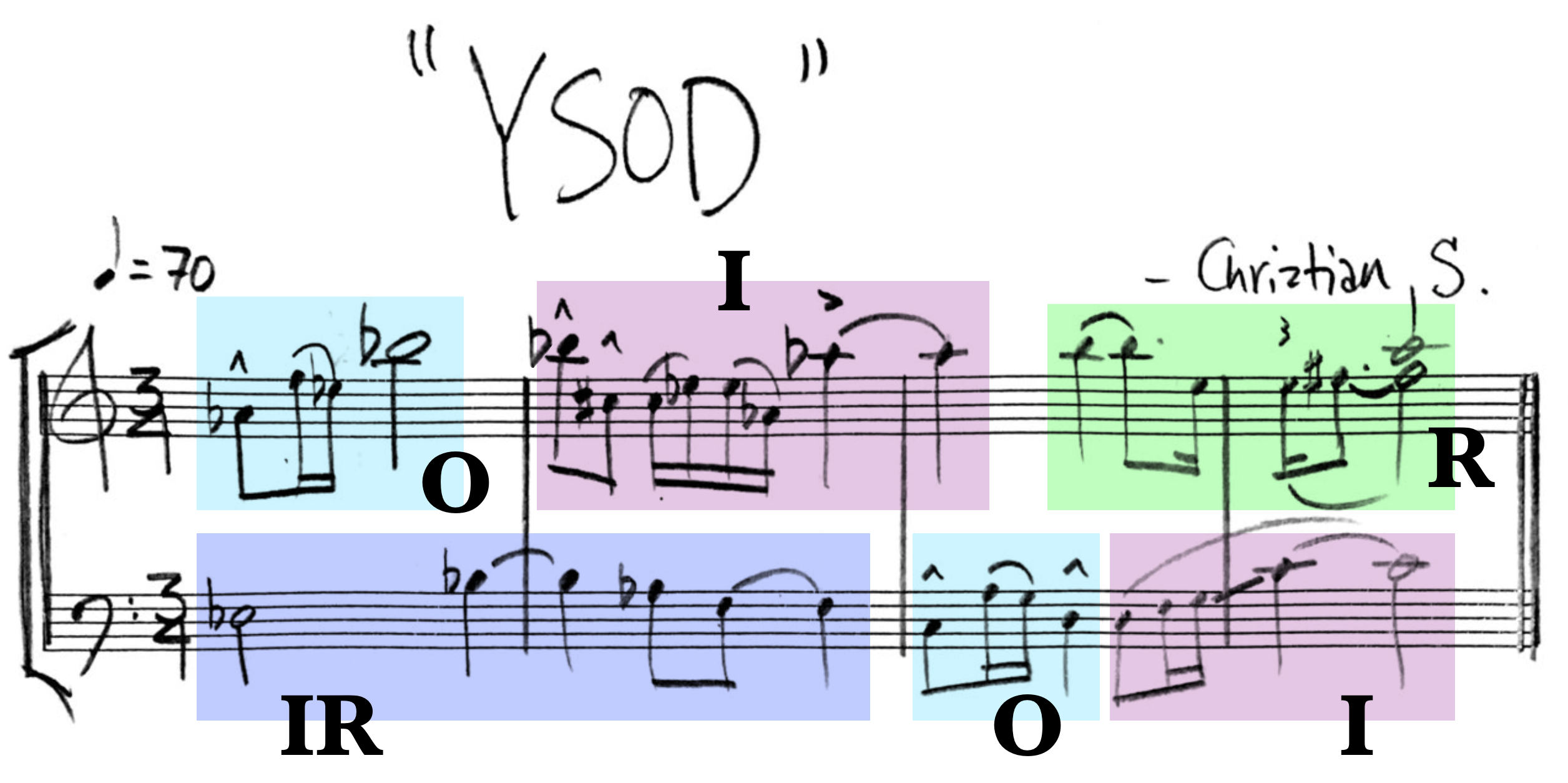

Even though there's no rule dictating to start with the origin sequence, I kind of liked starting there, so I grabbed a piece of manuscript paper and jotted it down.

One thing to bear in mind here is that while I did use the guitar to find the right motif, I put the guitar down after that, and wrote the entire piece on paper, just using "gut" and acquired skills with respect to "knowing" how certain notes sound together/in succession etc.

This is mainly because composing with the guitar seems to immediately limit my choices to guitar-idiomatic stuff, whereas on paper, nothing stops me from putting crazy and seemingly un-playable stuff on the page.

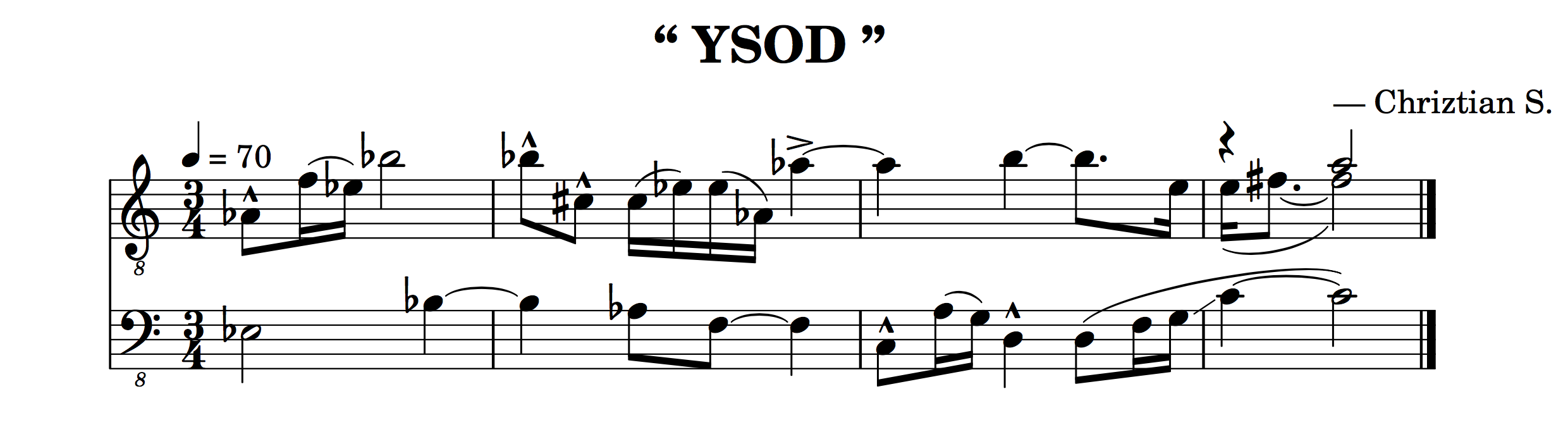

I decided to create a short jingle or maybe an intro, with two voices and here's what I came up with:

Here it is again, highlighting the individual sequences:

As you can see, I managed to get each of the four sequences in, with repeat occurences from origin and inverse.

Note that you're allowed to transpose the sequences, meaning that any sequence can start on any desired pitch; which, incidentally, makes it a lot harder to debug and/or fact-check, so-to-speak :-)

You're also allowed to repeat a note (any number of times and in any octave) before playing the next one, so if you were counting the notes and wondered why the first appearance of inverse has 7 notes instead of 4, I've prepared an extra little visual to show the repeating notes:

Audio

Now, I happen to just love music in manuscript form — even before I understood how to translate the little black dots to the clarinet (before taking up guitar) I used to love "reading" the music I was listening to. I quickly learned that the number of dots per line was pretty much a sign of how busy the musicians were, and I used that to "navigate" — coolest moments were when I'd flip the page and saw that in about 20 seconds things would start to get really busy! Felt almost like a time-traveller :-)

But hey, to the vast majority of people, music is actually enjoyed with the ears, so I needed to record the thing so we can all hear how a YSOD can sound. I tried a couple of apps on my iPhone together with an iRig contraption for getting the guitar's output; I've put the recording on SoundCloud for everyone to hear.

So there you have it - I completely managed to forget all about the code that didn't work, and instead I got to rediscover something else I really love doing.

Bonus Track: Engraving

So as it happens, I have a programmer's brain as well as a musician's, so of course I've dabbled with a way of notating music with some sort of code that a computer understands, from MIDI to XML and back again. Years ago, I stumbled upon this cool little project called "Lilypond", which is actually a compiler for music notation! It takes care of the hard engraving process, when you feed it a (very) special "code" format.

I had to try it for this just to see how it would rack up compared to my own hand-written notation (TL;DR: It doesn't by any stretch :-)

Here's the code for it:

(Of course there's a PasteBin-equivalent for Lilypond called LilyBin so here's a link to that as well, if you feel like playing around.)

Here's how it renders:

While I prefer my own hand-written version, I'm pretty impressed with the result — it's one thing to have learned when to add a tie or an accent; or when there's a couple of notes close to each other at the same time, where to put the dots, slurs, stems etc. - but for a computer program to deduct all that information and render something that any music-reading musician can just play, is pretty remarkable.

I've set up a GitHub repository with all the files for this, so take a look if you like.

-

A Yellow Screen Of Death is the .NET Framework's error screen, telling you that a runtime error has ocurred. We hatesss them! ↩︎

-

Some 20 years ago, from 1994—1998 to be exact. ↩︎

-

Sidenote: Years ago I tried another variant while I was studying music, where I used a "normal" 7-note scale to create a piece of music while using the rules of 12-tone music. So this was not all-new territory for me; though having only 4 notes to start with is quite a limitation :) ↩︎

-

The only one I trust to have those skills would be @clauswitt :-) ↩︎

-

I realize not all readers would necessarily know anything about music notation, so in case you're wondering - d♯and e♭ are interchangeable - the first describes the note a halfstep above d whereas the second describes the note a halfstep below e. So basically ++two and --four in programmer lingo. ↩︎