Previously I covered the basic concepts of Docker. If you followed the examples through you would have created a database container, and a website container running Umbraco 9, and run them together in the same Docker network. I didn't cover networking, or another concept — Dockerfiles — in a lot of detail as I wanted the first part to have a low barrier to entry.

In this second part we will cover these concepts in a bit more detail, and cover a couple of other concepts including:

- Docker Volumes: A way to share data between containers, and to persist data between restarts.

- Docker Networking: More details around how to connect containers to each other.

- DockerFile: Defining the components and build steps required to build a container image.

- Docker Compose: A tool to manage multiple containers in a single file.

Prerequisites

It's expected that if you have followed the first part of this tutorial, you have already installed Docker, and have created a database container, and a website container running Umbraco 9. This article will build on the code used from article 1, so if you haven't completed that first part, you should go back to Article 1.

Umbraco Version

This article uses version 9 of Umbraco, which does not currently support SQLite, but this is a feature of Umbraco 10, which will be released during Codegarden 2022. I will update this Github repo to use Umbraco 10 when it is released.

It's all about storage

Containers have a problem - they can be sometimes ephemeral, and if they get deleted for any reason their file contents are gone. You don't want to think of them as analogue to a physical or a virtual server. If you were to delete a container instance and recreate it, you lose all data which has changed from the original container image — it's not persisted, and that's by design.

This may not be a problem when you are hosting a static website where all code and images are built into the image, but if you were hosting a database server in the container, that's less useful — any databases which were created after the container was created will be lost.

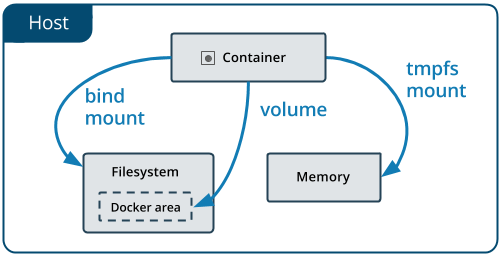

There are several options for managing storage in containers, and these are through Mounts, and there are 3 main types:

- Volumes: These are stored in the host system filesystem managed by Docker, and typically these aren't available to non-docker processes. This is the recommended way to access storage outside the container instance.

- Bind Mounts: These are basically like Volumes, but are not restricted — so they can be anywhere on the host system. This is useful if you want interaction between processes on the container as well as processes on the host system.

- Tmpfs: These are stored in the Memory of the host system, and are never written to the filesystem. They are by that nature extremely fast, and are useful for temporary storage, but should not be used for long-term storage.

I will focus on Volumes, as they are the most common option, and the recommended way to access storage outside the container instance, and used in the vast majority of cases.

Docker Volumes

If you delete a container with a volume, any data which is stored in that volume will persist even when it is deleted, but any data stored in the container is lost. Additionally if multiple containers use the same volume, they will share that data. This has the added benefit of making it easier to share data between containers, and to persist data between restarts.

Volumes can be created in several ways, but for simplicity I will focus on 2 methods.

- Using the docker run -v command

- Using docker compose files (see later in this article)

In the first part of this series we ran the Umbraco website container using this command:

docker run --name umbdock -p 8000:80 -v media:/app/wwwroot/media -v logs:/app/umbraco/Logs -e ASPNETCORE_ENVIRONMENT='Staging' --network=umbNet -d umbdock

This created a volume for the Umbraco logs directory and the media folder — both would persist between restarts.

Networks

In the previous part I covered a little about docker networks, and I'll add a little to it in this part — but there's a lot more to networking and it's a huge topic, so I'm only going to cover enough to be dangerous 😊.

Ports

Before diving into networks, we need to touch on ports - when a container is created, you define which ports internally are accessible outside the container. If you don't, the container will still run, but it won't be accessible from outside the container. In the CLI, ports are exposed using the -p flag, and are defined as host:container.

In our previous example we exposed port 8000 externally mapped to port 80 internally on the container for the website containers, and port 1400 externally mapped internally to port 1433 for the database container.

docker run --name umbdock -p 8000:80 -v media:/app/wwwroot/media -v logs:/app/umbraco/Logs -e ASPNETCORE_ENVIRONMENT='Staging' --network=umbNet -d umbdock

docker run --name umbdata -p 1400:1433 --volume sqlserver:/var/opt/sqlserver -d umbdataBridge Network

The default network in docker is "bridge" networking, which is automatically assigned to containers unless specified. All containers in this network appear on the host IP address, but that also means that if you have multiple website containers, you can't use the same external port for all of them — you will need to map a different port per container.

Default Bridge Network

The standard bridge network also doesn't let the containers communicate with each other using DNS, only by their internal IP address, and that's not something that's available to you at design time, only run time. If you wanted to keep using the bridge network, you will need to query the container IP address at runtime and use that to address it. Every container can see every other container in this network, but that usually isn't a problem. The IP address assigned will also change on all container restarts, so you can't rely on it being the same every time.

User Defined Bridge Network

The main difference with this sort is that you can specify a name for this network, but also that containers can access each other using their container name. This is great when you are creating a connectionstring for a website to access a database for example — so even though the IP address isn't going to be static, it doesn't matter. You access the container you need by its name.

These are also called Custom bridge networks, and the other thing docker does is isolate all custom bridge networks from all others. Any container outside the network won't be able to see containers in the network, they will be isolated.

Host Networks

Host networking is used when you have a container which basically needs to communicate as if it's running natively on the host computer — it will be able to access the hosts network. That's evident when you create the container — you don't need to specify any port mappings. Ports on the container are natively mapped to the host computer network

There are other networking types available, but those are less common, and are more advanced, so I'm not going to cover them here — if you want to find out more there are reference links in the footer.

Dockerfile and Docker Compose

Now that I have covered networking, and storage the last part, and possibly the most important covers Dockerfile and Docker Compose. The Dockerfile is a file which is used to build a container image, and the Docker Compose file is a file which is used to manage multiple containers in a single file. Thus you define each container in your application with its own Dockerfile, and you define the application as a whole with Docker Compose.

Dockerfile

In the previous article we created 2 docker containers, each with their own Dockerfiles. These Dockerfiles have one purpose — to define the image that the container will use. It starts with defining what the base image will be, and then it defines the commands that will be run when the container is started. The advice I've always been given is to use many small steps in the Dockerfile, and to use a consistent image for containers. The aim is always to keep the container image size as small as possible to keep resource use down and set you up for scalability from day 1.

Additional to defining the starting container size you can really do everything you can in the command-line in a Docker File including and not restricted to:

- Run commands, which in turn can do basically anything you want including:

- Downloading dependencies and installing packages.

- Compiling code.

- Running tests.

- Attaching databases, starting indexes.

- Copying/deleting files, images, directories.

- Anything you can do on the command line.

- Defining environmental variables.

- Expose ports from the container to the outside world.

- Defining the start-up command for the container, the process which will run when the container is started.

With a docker file we can create a Docker image, which can be saved locally, or pushed to a private or public repository, and re-used by other applications.

You can browse the contents of both DockerFiles to get a breakdown of what each is doing.

Docker Compose

Once each container has a Dockerfile, the next and final piece of this walkthrough is the Docker Compose file, which will be the first new file we have created, as so far we've only gone through explainers of what we did in the previous article. Now we're going to create a docker file which will link the two containers together and allow us to start them up and stop them together.

First copy the docker-compose.yml file from the Files folder into the root. Opening this file you can see it's broken into 3 sections.

Services

This defines the containers we want to make up our application. Each service defines the associated docker file it will use, the ports it needs to expose, the volumes it will need, the network it will be part of and any specific environmental variables.

The ability to set environmental variables is important since it allows us to also use config transformations to define a connectionstring for the "Production" environment vs the staging or local dev environment.

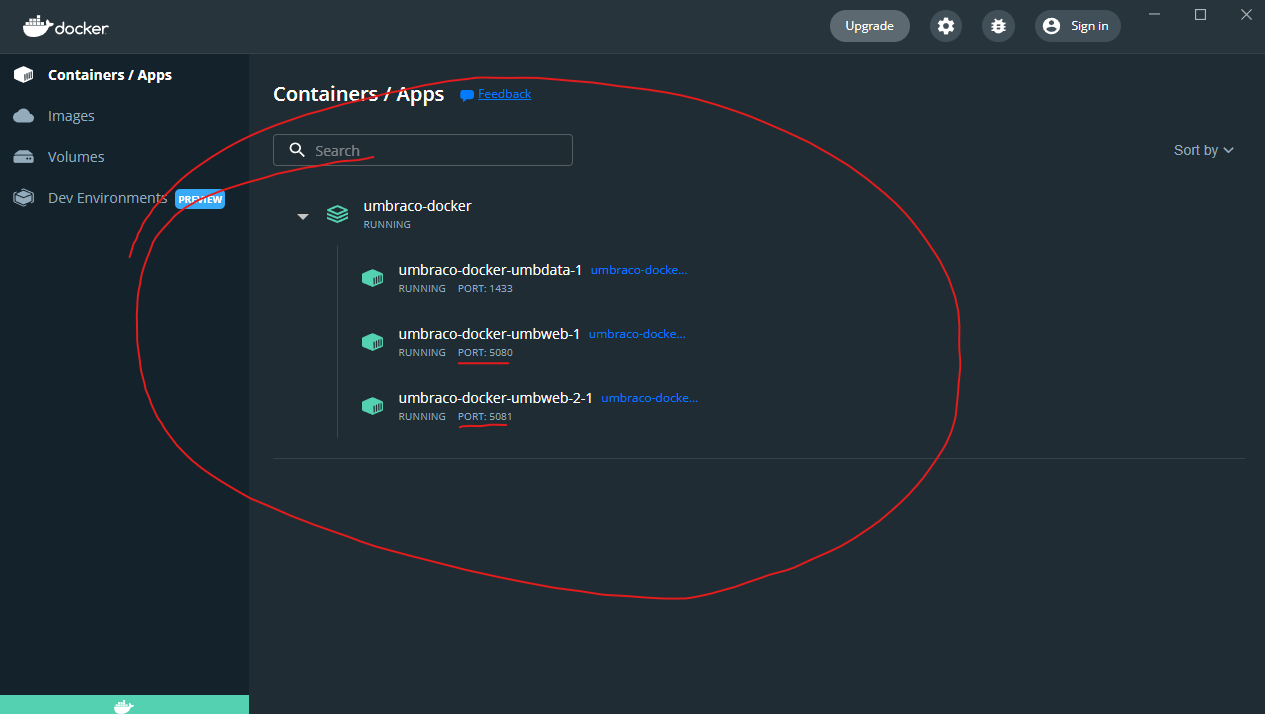

There are 3 services defined - the database and the two website containers. Each is named accordingly, and has a list of all the relevant ports, volumes and network - the two website containers are very similar - only really differing in that they expose different ports. If you looks at both the ports section of the two websites they have different external ports - umbdock exposes port 5080 and umbdock exposes port 5081.

Volumes

Each service refers to the volumes it uses, but these need to be defined in the Volumes section of the docker-compose file. You can define the name, the location and type of the volume in this section.

In this docker compose, there are 2 websites running attached to the same database server, and due to their shared volumes they will also share the media and logs folder, so any media added to one site will be available to the other site server.

Networks

As with volumes, each service uses a specific network, and these networks need to relate to the networks section of the file.

Starting things up

When you're ready to start up the application there are 2 steps we need to take.

First copy the docker-compose.yml file has been copied to the root of the application.

The next thing we need is to create a configuration file for the production environment, which will be what we will be running — copy the existing appsettings.Staging.json to a new file called appsettings.Production.json.

The contents of this file will be the same as the staging file, it's just there to illustrate the ability to change settings with environmental variables.

Once that's done, run the following command it will start things up.

docker compose up -dThat's the extent of the user interaction in this part. That's it — this will start your entire application in disconnected mode, which means it'll continue to run after you close the terminal.

If you look at Docker desktop, you should see your application listed, but it will appear differently to how it might have previously, since it is now being created through docker compose, so all the containers are grouped together.

Docker Compose

You'll be able to access your website at http://localhost:5080 and the 2nd site at http://localhost:5080. This is a typical arrangement where you might want to load-balance your Umbraco content delivery websites, or have a separate editing and publishing environment — the details of how to load balance is beyond the scope of this, but there are some great courses available from Umbraco if you want further info.

That's it - all done!

Hopefully you've enjoyed this experience, and have learned a little about how Docker, and docker compose can be used to host and test applications!

Troubleshooting

If you ever need to stop the application and take it offline, run the following:

docker compose downIf you wish to wipe the slate clean, you can remove all your containers, images and volumes by running the following.

Note: This will remove all unused images and volumes. If you have images from other applications you want to keep, don't run this.

docker compose down

docker compose rm -f

docker image prune -a -f

docker volume prune -f References

- Docker Volumes : https://docs.docker.com/storage/volumes/

- Docker Network : https://docs.docker.com/network/

- Bridge Network : https://docs.docker.com/network/bridge/

- Host Network : https://docs.docker.com/network/host/

- Dockerfile : https://docs.docker.com/engine/reference/builder/

- Docker Compose : https://docs.docker.com/compose/

Further Reading

- Docker Swarm vs Kubernetes : https://circleci.com/blog/docker-swarm-vs-kubernetes/